Fall 2020

Novel Writing -- WRIT1-CE9355

Meredith Sue Willis Home Syllabus

Various NYU policies Individual Presentation Dates for Critiquing

Check this site frequently for changes in readings

and for optional informationupdated 11-18-20

Optional text: Ten Strategies to Write Your Novel by Meredith Sue Willis.

Available from the NYU Bookstore, the publisher, and the usual online suspects.

Good Luck with your Novels!

Go Directly to Current Week

Presentation/Critique Schedule

Do you know these novelists?

See below for names

Current Week

Syllabus

Presentation/Critique Schedule

Various Things to Read (all optional)

Malcolm Gladwell on the four types of detective/mystery.thriller novels.

Read this on Story, Plot, and Character: Dennis Lehane appreciates Elmore Leonard

Suzan Colón's "Stakes" Method of Outlining

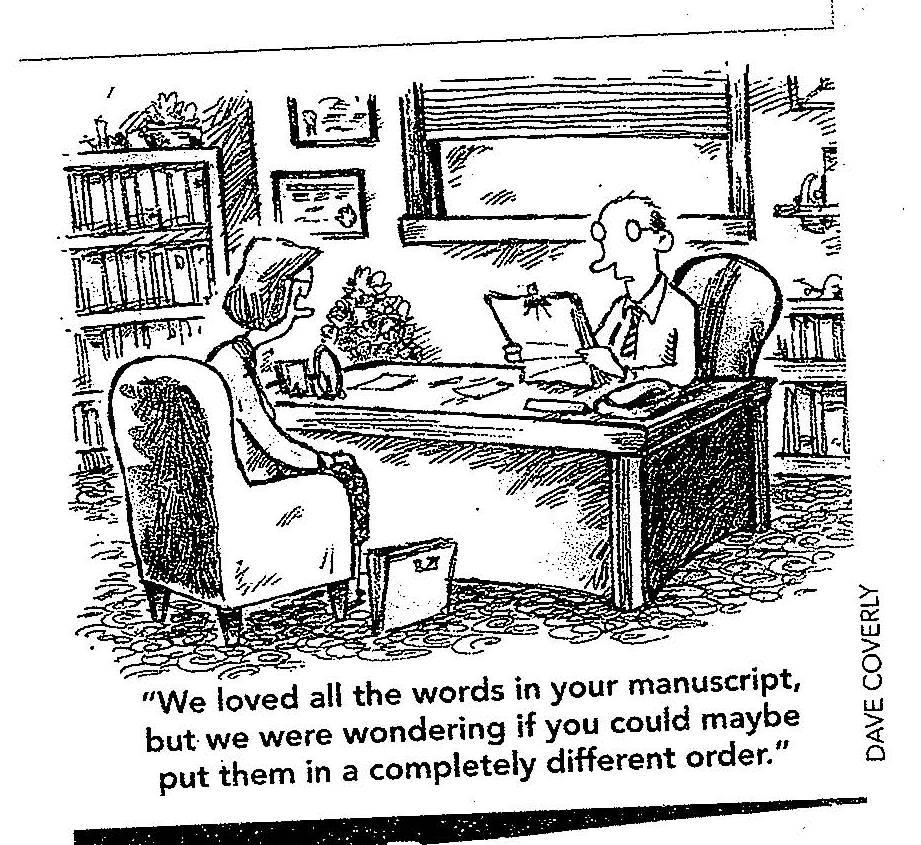

$4.99 Downloadable Book about the Process of Publishing

Alexander Chee on how he writes his novels

Here's a link to an article about a former NYU novel class student Marlen Bodden.

An article by Jake Wolff with about doing research for fiction

Do you need ideas for starting your novel? Check out MSW's article online from The Writer "How to Get a Novel Started."

A critique of the workshopping with a silent author by Beth Nguyen

Piece about getting early readers for your manuscript: don't miss the section on special "sensitivity" readers and the responses in comments!

The Raised Relief Map-- a drafting technique for creative writers

Check out Harvey Chapman's Novel Writing Help. He's an oddity who seems to me more interested in how fiction works (and teaching it) than in writing it. He has a gruff self-consciously masculine style, but is definitely worth a look.

Epigraphs

My current favorite opening line of a novel: "Frederick J. Frenger, Jr., a blithe psychopath from California, asked the flight attendant in first class for another glass of champagne and some writing materials."

Charles WIlleford, Miami BluesAnother good one: "Later, as he sat on his balcony eating the dog, Dr. Robert Laing reflected on the unusual events that had taken place within this huge apartment building during the previous three months...."

-J.G. Ballard's High RiseQuirky quotation: "To all the devils, lusts, passions, greeds, envys, loves, hates, strange desires, enemies ghostly and real, the army of memories, with which I do battle—may they never give me peace."

-Patricia Highsmith, diary entryOld fashioned advice: "A novel should give a picture of common life enlivened by humour and sweetened by pathos."

- Anthony Trollope in An Autobiography

NYU WRIT1-WRIT1-CE9355

Novel Writing (Fall 2020)New York University Fall 2020

September 9- November 18

(No class Nov. 11)

Wednesdays, 6:30 PM - 8:50 PM

Online-Zoom

Instructor: Meredith Sue Willis

E-mail: MeredithSueWillis@gmail.com

Optional Text: Ten Strategies to Write Your Novel by MSW

( Available NYU Bookstore, all the usual online suspects including Bookshop.org.)

Course Business (for NYU Rules 'n Regs Click Here)

This class welcomes beginning novelists, but is also aimed at writers who are well-underway on a novel and need further discussion and stimulation to continue or restart. We will cover a lot of basics fast, beginning with a survey of common terms for discussing novels and a look at novel structure in general. If you feel you need more of the basic terminology and ideas, please take a look at the teacher's book, Ten Strategies to Write Your Novel.

For those with longer or revised manuscripts, this course may be repeated.

Note to those new at novel writing: you'll probably get most out of this class if you do the weekly assignments. They will give you several scenes or fragments that can become the scenic frame work of your novel.

Note to returning students and others with a novel-in-progress: The fall section of this class follows a series of assignments aimed at getting a novel started. For those with a novel already in process, use the assignments-- or substitute passages from your project--to move your book forward in whatever way works for you.

During the course, you may bring a total of up-to 50 manuscript pages for critique (some of these pages will be for whole class critique, some only for the instructor). A page is comparable to a double spaced one sided sheet of paper with one inch margins all around and Times New Roman 12 pt. font. It is roughly 300 words.

All writing and presentation selections should be from the novel you're working on.

This syllabus will be updated regularly online, so please check this web page at least once a week. Access to the website is also available from MSW's home page. Look at the top left.

Assignments go only to MSW. Anything you turn in to MSW, however, including the presentation pieces and optional homework, counts towards the total of 50 pages to be reviewed during the semester. You may turn in work weekly or less often, but please let MSW know your plan so she doesn't get swamped,

Assignments are due as noted on class web page/syllabus: "Writing due:" means the homework (or your substitute pages) is due by class time on the given day. This is as if you were bringing in hard copies to a non-virtual class. You have a week to do the work, so try to be timely. If you want to turn in more at one time, but fewer times, that's fine. Just let me know.

Please be prepared to discuss the work of classmates when they present.

You will receive a grade for this course unless you request a NonEvaluative mark. For the Non-Evaluative, please see the attached form. A copy of this request must be filed with the department. Send it by e-mail to kf38@nyu.edu.

No letter grade will be given below a B. To earn a B, you must complete 50 pages to the professor's satisfaction plus present work for critiquing by the class at least once. To earn an A, you must complete the 50 pages, present work for critiquing by the class at least twice, show evidence of having done any outside reading, plus participate fully in class discussions. For all grades, attendance is required.

It should be noted that all NYU policies on academic integrity, i.e., plagiarism, are fully in effect in this course. For NYU policies, click here.

Disclaimer: This syllabus is subject to change due to current events, guest speaker schedule changes, and/or level and interests of students.

- ANY QUESTIONS???

Technical Information, grammar, and formatting

Getting the right spacing between paragraphs in Word. Word's default spacing is block paragraphs, which make your paragraphs look like business letters. Narrative prose needs to flow. Use no extra space between paragraphs (unless you have a time gap or stylistic reason). Indent each paragraph.

Look over conventional editorial marks.

A piece from The Guardian on adverbs

Check out Reedsy.com for free lessons and information on hiring publishing specialists (and more)

Schedule and Plan of Classes

Session 1. 9-9-20 Introduction

and Focus on Sense Details

Assignment Due Before the First Class: For the first session, please e-mail the instructor a one page summary or outline of the novel (if you are just beginning your book, do this as a hypothesis) plus the first page to give everyone in the class a taste of your prose style.

Please send a copy of your two pages to all students in the class. I already have them.

Reading Assignments:

1. Two chapters in Ten Strategies: "Strategy 1: Separate Process and Product: and "Strategy 2: Taste It, Touch It Smell It..." (Optional).

2. Advice for Books to Read to Learn to Write Novels

3. Click on the "Read an Excerpt" at this link link. Or (optionally), you may read the full version In Ten Strategies to Write Your Novel, "Strategy 1: Separate Process and Product.")

I.

Business I: addresses, e-mails, etc.

Structure of the course Mini-lectures; critiques; in-class writing. Discussions (but not as open as they can be in person!)

II.

First introductions Go-round: Name you want to be called. One sentence about you (anything but your writing career and novel). do a go round on novel later.

III.

Business II: NYU business

NYU business and more procedures: All your questions answered.

IV.

Questions about Zoom? Other?

V.

Vocabulary Lesson:

1. Process and Product

2.. Macro and Micro. Big issues like structure; but also revision and the importance of the concrete. In-betrween macro and micro comes the scene, which is the major building block of novels (as of film and theater).

3. Terms for Novel Writing that we'll use in this course. (Feel free to save or sprint any pages you want to use)

4. Of endless, enormous importance: Point of View in all fiction.

VI.

Everything is built with concrete observation and sense details.

-- Read aloud this 19th century description of a day at the end of July. Note smells, lots of smells: The thirtieth of July

-- Read this one: no visuals at all in this place: from "Consultation" by Ariel Dorfman.

VII.

WRITE a moment in your novel when an important character encounters an object. (This can be quotidian or important--attractive or repellent--food, jewelry, an African violet plant, a weapon). But use all your senses....

VIII.

Share a couple

IX.

Break

X.

Go-round on your novel. Don't say if you are well along or just beginning.

Give its genre, if you can.

How long the book will be in its final form.

What is its final form?

Who is likely to read it?

Check out Types of Novels.

XI.

SCHEDULE PRESENTATIONS FOR CRITIQUE.

We need two people for next week. You'll get at least two turns. E-mail attached work, as a Word file or .pdf to whole class & teacher by (at the VERY latest) Sunday night before your presentation so people have time to look at it.

XII.

WRITE

List Three Essential Scenes from your novel. Make them up if you have to.

XIII. For next session

Writing Assignment due 9-16: The first time a character visits a place in your novel– describe the place using all five senses if possible. There may be a lot of emotional content or not.

Reading and Other Assignments due 9-16: Please send everyone in the class a copy of your one page summary/outline and your first page. Also, please at least skim over these as an introduction to your classmates and their novels. Look for further readings on the website later in the week.

Session 2. 9-16-20

Developing Character Through

Physical Description & Physical Action

Assignments due:

Writing Assignment due: The first time a character visits a place in your novel– describe the place using all five senses if possible. There may be a lot of emotional content or not.

Reading and Other Assignments due:

Read pieces for presentation for tonight.

Read "Strategy 3: Explore Character from the Inside Out" in Ten Strategies (optional).

Read these short pieces of character development through description, action, and monologue: "Old Florist" (poem); "Caddy Jellyby;" "Alice;" and others here.Please look over the summaries and first pages as an introduction to the class's novels.

Please send MSW possible dates to present work for critique for the first time. (We'll pick second dates after everyone has a first one.

2002 television version of characters from Daniel Deronda

I. Business

Who wants/doesn't want a grade

Date for your first presentation Use the web page, not the NYU Classes Syllabus

Weekly (homework) assignments, for those doing them, are due on class day. They should should be about 3 pages (up to 600 words).

Presentation pieces are typically 5-7 pp, no more than 10. Fewer is okay too. These are due by the Sunday night before class.

You may turn in up to 50 pages total to MSW. Less is okay too.

Formatting– 1 inch magins, double space, etc.

II. How was the Homework?

It is, at bottom, an exercise in character building, even though it is about place.

We will do a little later a similar exercise with descreibing people directly, from the outside, and the chapter for today in Ten Strategies "Strategy 3" chapter is about exploring character from the inside out, monolog.

Just for fun, if you are stuck with a character in any way, try a monolog for him or her (more about that in a later session), and also a real quickie, take a look at characteristics.

III. WRITE

Quick writing: using that list, think of a minor character in your novel and choose 5-7 things from the list and write them down about that character.

IV. What do you want from this course? (Go-Round)

V. How do we evaluate fiction?

How do you evaluate fiction in preparation for critiquing?

Separate line editing from conceptual editing

Offer any expertise you have?

What do you want to know more about?

Points for novel critiquing.pdf

Writer should ask for specific kinds of critique

Be prepared to talk;

write a holistic note;

use "comments" in Word

scan in and email.

Ask writer for snail mail and sent your notes that way.

VI. Presenter I – Suzanne

BREAK

VII. Presenter II: Alison

VIII. WRITE a physical Action

Write about a character in your novel running. If you don't have such a scene, add one--maybe from the part you haven't written yet.

The character may be fleeing danger or trying to make a plane or in a competition or playing with a pet. Write for 3 minutes seeing the action from the outside, concentrating on the movements and sounds, possibly using the screen technique above.

IX. Describing Physical Action

Writers who are naturals at dialogue and brilliant at structure and metaphor often have difficulties when their characters need to make a sandwich or kiss their lovers or strike out in a softball game. People write physical action in many ways, but the default is to describe it cleanly and smoothly, so that a reader can visualize what's happening and not have to get into trying to figure out whose fists smashed whose nose.

It is not as easy as it seems.

Here's an example that is plain and brief and cinematic in its small way. It was, in fact, transferred almost gesture by gesture to film.

The Don, still sitting at Hagen’s desk, inclined his body toward the undertaker. Bonasera hesitated then bent down and put his lips so close to the Don’s hairy ear that they touched. Don Corleone listened like a priest in the confessional, gazing away into the distance, passive, remote. They stayed for a long moment until Bonasera finished whispering and straightened to his full height. The Don looked gravely at Bonasera. Bonasera, his face flushed, returned his gaze unflinchingly.

-- Mario Puzo, The Godfather, p. 30

In general, physical action-- whether making tortillas or running for a bus or slashing with a knife, whether about making love or committing a murder-- works best when it is simple and sharp. The fewer words the better. Obviously this is a rule that has been broken often and to good effect, but start by trying to transfer what you see in your mind simply and clearly to the reader's mind.

One excellent technique to help you do this is to close your eyes and actually visualize a movie or TV screen. Watch your characters do their actions on the screen, and then write what you saw. Keep in mind that once again we are talking about revision, not drafting: I don't care how bad your description of action is in your first draft. Get it down first, then make it better.

Here are two passages of action. The first one is, which you are welcome just to skim, is a classic not-so-artistic passage of action from an old cowboy novel. It feels long and loose now, but Louis L'Amour was extremely popular in the last century

The second one is rather poetic, but also very easy to visualize. It also is about the narrator's experience, and and her feelings about dance and her dance teacher.

A Fist Fight from an old Louis L'Amour Novel

He Goes She Goes

X. Writing Assignment due 9-23-20:

Describe a character in your novel using all the senses, but emphasizing the ones other than sight. If your novel is told from a first person point of view, have that first person do the describing. If it is told in a close third person, have that person do the observation. Use the descripton to go deeper into both characters. Give the observer insights about the character based on the clues they see. Also have the character do something physical. Include anything else you want--a conversation with another character, a monologue, narration.

Presentation Schedule

Session 3. 9-23-20

Dialogue and Scene

Assignments Due:

Writing Assignment due: Describe a character in your novel using all the senses, but emphasizing the ones other than sight. If your novel is told from a first person point of view, have that first person do the describing. If it is told in a close third person, have that person do the observation. Use the description to go deeper into both characters. Give the observer insights about the character based on the clues they see. Also have the character do something physical. Include anything else you want--a conversation with another character, a monologue, narration.

Reading Assignment (optional): The building block of novels. Ten Strategies, "Strategy 5: Master Dialogue and Scene." (optional)

More reading: If you haven't read it yet, read Scene and summary. What is Scene? Why is it important?

Also look at this material on use of present tense: http://www.meredithsuewillis.com/materials.html#presenttense.

To learn techniques for writing inner dialogue, see The Editor's Blog on choices for writing "Inner dialogue." For a more concise version of this information, see Grammar Girl. (optional)

I. Business

• Is it clear about when you'll get your homework back?

• I'm trying to do home works with Word "comments," but so far I'm doing critique pieces by hand.

• Who wants/doesn't want a grade–Linda, Dreama, David?

• Michelle for 9-30

• Sign up to present sheet– Those who want second dates, e-mail me.

• Remember: it's your choice to do the assignments or substitute, but everything should be from your novel.

•Look over conventional editorial marks.

II. Point of View

We didn't really talk fully about Point of View yet.

It's probably the most essential element to knowing how to tell your story. Who is telling it? At what distance? In other words, you can be in first person, telling from a 50 year old's perspective. Can you also give (why or why not would you) what the person experienced as a 10 year old?

Let's look at a couple of materials some of you may have seen in the past, but it makes the point:

1. Point of view chart–just more vocabulary, really.

2. Then an example I'm very fond of where omniscient sounds amateurish.

III. WRITESomeone in your novel meets someone important for the first time. How do you tell it?

IV.

Respond? Share?

V. Some things I'm noting as I look at your work:

A. Grammar in fiction: watch out for too formal, especially within quotation marks.

B. Use of foreign languages:

"Our gallery was located on the ground floor and we had floor to ceiling windows which gave him 'a portal to eager woman.' His German words, not mine."

Is it German language? Or German grammar?

So how do you show foreign languages and accents in your novel?

VI.

Here's a page of ways of putting Spanish into a scene.

VII. Presenter-- David

Break

VIII. Dialogue is where it all happens.

Dialogue creates the illusion of the real world--closer to the thing it imitates (people talking) than any other element of fiction.

The observation of details comes to us in real life in an instantaneous glance.

A physical action like a sword thrust in real life is a very different matter from a sword thrust described in words.

But read dialogue aloud, it takes something close to the same period of time as if the conversation were happening in real life.

This also accounts for some of the difficulties of writing dialogue: amateur novelists tend to think that if they can simply transcribe the way people talk, they are writing good dialogue. In fact, of course, realistic dialogue in a novel is an illusion.

Getting down all the words the people say is a good technique for drafting, but the best dialogue in novels is usually shorter, tighter, and more dramatic. A transcript of a conversation (think of a court proceeding) is tedious to read. It lacks the cues for how things are said, tone and gesture. It lacks what is called the gesture line, the actions that make it easy for a reader to visualize.

A transcribed "real" dialogue also has too many words. There are phatic statements, fillers, grunts, and coughs. We tolerate many more words when we speak and listen than when we read. Novels intensify and sharpen conversation and heighten the intensity of the words. Even if the conversation is meant to show how inarticulate the speakers are, their inarticulateness is going to be more sharply demonstrated than in real life.

Please click on Yonnondio and read the little scene from a novel about the Depression in the 1930's in the U.S. This is, pedagogically speaking, about what all goes into a dialogue (and makes it a scene).

IX. Write

Write this on a piece of paper:

It's been a long time.

Yes, it has.

Is this it?

I guess it is.

Add whatever you need to make it into a scene that might be used in your novel.

X.

Responses? Share?

XI.

Writing Assignment due next week: Write a scene focused on dialogue--and the things in dialogue besides the words said.

Presentation schedule below

Session 4. 9-30-20

More Dialogue; More on Characters and Minor Characters

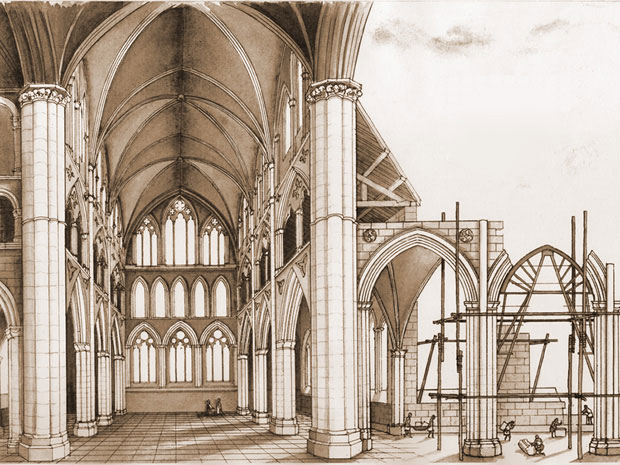

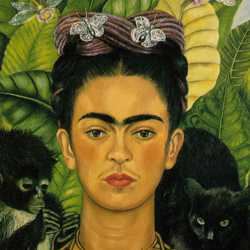

Top: minor characters from movie version of Hunger Games; second row: Frida Kahlo, who made a character of herself in her art;

a scene from movie version of Hemingway story, "The Killers;" Fan-fiction characters

Writing Assignment due this week: Write a scene focused on dialogue--and the things in dialogue besides the words said.

Read the material on dialogue at: Dialogue Tags ; Types of Discourse; and "Dialogue: The Spine of Fiction." (article by MSW about dialogue online).

I. Business

Has all the homework arrived? Are we caught up?

Some of you haven't written me how you plan to respond to the presentation pieces, aside from class discussion.

Alison Hubbard presentation for 10-7-20 (arriving by Sunday night)

Changes for presentation schedule? Does everyonle have two times, if they want it?

Remember: it's your choice to do the assignments or substitute, but everything should be from your novel.

If you haven't yet, take a look at this material on use of present tense: http://www.meredithsuewillis.com/materials.html#presenttense.

Here's an article on editing errors to avoid. It appears to be aimed at people who are self-publishing, but whenever you present work to others, it has become a product and deserves at least some editng: Ten Editng Errors to Avoid.

Finally, below is one of my grammar pet peeves:

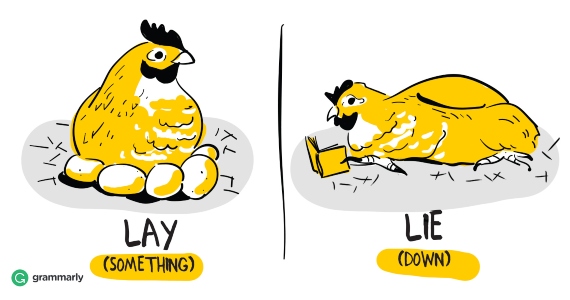

II. Mini Grammar LessonMini-lesson on Lie versus Lay

– Today I lie in my bed; yesterday, I lay in my bed. In the past, I have lain in bed till noon.

– As we speak, I lay the paintbrush on the table. I laid it there yesterday too, and, in fact, I have laid it there many times.

– As we speak, I lay it down, and then the paintbrush just lies there.. But when I laid it down yesterday, it rolled off the table and lay on the floor.

Confused? Paintbrushes "lie" on the table or floor, but you "lay" the paintbrush down on the table. Then of course, it just "lies" there.

The really confusing part is the past tenses: "I laid the brush down beside the paints, and it just lay there." One verb has an object; one doesn't. Many, many people do this in a grammatically incorrect way.

For those of you who hate grammar and don't really care, take heart: there is an excellent chance that in another ten or twenty years, usage will have changed.

One current dictionary ( Random House Unabridged Second Edition) explains, "...forms of LAY are commonly heard in senses normally associated with LIE. In edited written English, [however,] such uses of LAY are rare and are usually considered nonstandard."

III. Some issues with dialogue writing.

1. Here's a properly formatted piece of conventional fiction.-- "The Two Lindas."

2.

In dialogue: tags, modification of tags and other verbs, and order of information. If time, look at "Avoiding Creative Dialogue Tag Syndrome."

3. Some various types of discourse, This is really about pacing, among other things:

when do you slow down, when speed-up a scene by narrating? You slow down time when you insert character's thoughts. So-called "direct" discourse is the closest to real time: a dramatized scene with what the people say and do.

4. Using dialect in writing Novels. We talked a little last week about how to indicate foreign languages in novels. What about different ways people speak? Dialects, speech patterns. regional phrases, words to use in created worlds (fantasy and science fiction, for example). Check out this article at your leisure.

IV. Write:

A conversation: two very different people, different ways of speaking, different desires, etc.

V. Share some?

VI. Break

VII. Presenter-- Michelle Vidal

VIII. WRITE/DISCUSS

Scribble down-- not a real writing:

If your novel were an animal, what animal would it be? Is it a pet, or, say a wolf with its foot in a trap

Discussion: What does your novel need from you?

IX. Next week....

Next week's Assignment: Write one of biggest conflict scenes in your novel: can be a war scene or a tense conversation-- but something important.

If you haven't already, read "Avoid Creative Dialogue Syndrome "

Optional Reading: "Strategy 4 Find Where You Standpoint of View." Also optional, this article on dialect.

Session 5. 10-7-20

Conflict in the Novel: First Thoughts on Structure

Still from Alfred Hitchcock's 1940 movie Rebecca with Joan Fontaine and Judith Anderson.

Daphne Du Maurier's novel came out in 1938.

Assignment Due: Write one of biggest conflict scenes in your novel: Can be a war scene or a tense conversation-- but something important.

If you haven't already, read "Avoid Creative Dialogue Syndrome "

Also optional, this article on dialect.

Australian Point of view on Novel Length! This also breaks down by genre, which is an interesting way to think about it: Article on novel length. The article is on the old side but still of interest for thinking about novel structure.

I. Business

Homework still getting back okay?

Next session's presenter-- Philip.

Marketing discussion?

Changes for presentation schedule? Does everyonle have two times, if they want it? (??Marc??)

II. Leftover from Last week:

Leftover from last week: Where to put description? Some excellent descriptions of characters in your pieces. But when do you do a full stop (as Alison did in her piece for today) to describe. In her case, it works, because it's the first time we meet an important character, and the first person narrator is paying full attention. You can also handle this, in revision, by breaking up trhe details with action and dialgoue. Look at "Where to put description.pdf"

Other consdierations to consider with description:

Don't forget details other than visual

When to "make it new?" As if seen for th first time in the world... (Alison's)

For minor characters, you can also just give a thumbnail–"He had a head like a Brazil nut."

Then merely refer? "So then Brazil nut head said..."

III. Write (logistics small)

We're moving into logistics, the coming week, small and large.

Here's an exercise in small motor action.

Look at the still from the 1940 movie above, particularly Judith Anderson's left hand, approaching but not quite touching heroine Joan Fontain'es shoulder. Clearly threatening, the space is everything.

Put a passage of gesture or action with hands In your nove-- a touch, cleaning a gun, punching in information on a keyboard. But break it down in more detail that you ordinarily would make a big deal of it.

IV. Share?

V. Presenter: Alison

darlin'

But also, how do you turn a story into a novel? Should you?

Conflict in a story is pretty much one crisis, one revelation or change or question answered, but a novel can have multiple, can follow the trajectorey of a live. Genre more often has a big crisis and out.

VI. Break

VII. The dialogue stuff we didn't do last week

In dialogue: tags,

Modification of tags and other verbs, and order of information.

Also, let's look at the overuse of tags and vivid verbs: just the beginning of this article: Creative Dialogue Tag Syndrome

Bottom line: go for invisible tags when you can, and when you do use a vivid verb ("shrieked," "begged," "murmured,") make it unusual and give it space to be powerful.

VIII. Issues on people's minds?

IX. Logistics LargerThe drunken Cowpoke.

Look at "The Logistics of Crowd Control Number II"

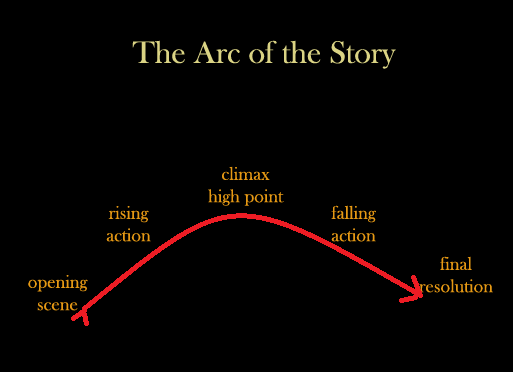

X. Conflict as the Arc of Story

For some commercially oriented information on a certain kind of novel structuring, take a look at this article from the Reedsy Blog.

XI. WRITE

A Dream for one of your characters

XII. Share

XIII. For Next week....

Writing Assignment due: Write a scene that uses a technique that is especially successful in fiction (interior monologue,memory, word play, flashback, summary, playing with time, etc.) .

Session 6. 10-14-20

Film Techniques for Novelists &

Things Novels Do Better than Movies

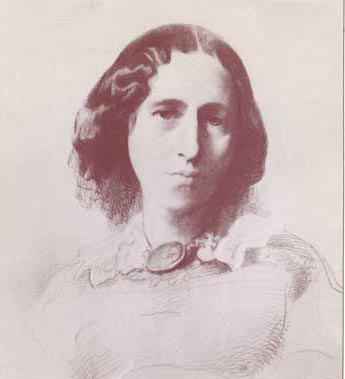

A few of the great ones from the nineteenth century: Austen Eliot, Tolstoy, James

Some Novelist whose works translated well to the screen: Dickens, Leonard, Puzo, Lee

Writing Assignment due: Write a scene that uses a technique that is especially successful in fiction (interior monologue,memory, word play, flashback, summary, playing with time, etc.) .Read flashback note.

Finally, see where or how you might use it in your novel. As part of a dialogue? Broken up into pieces and used in the narration and/or over several dialogues? In a phone or digital message?

Reading Assignment (optional) due today: Optional: Ten Strategies, "Strategy 7: Use Film Techniques."

Topic: movie techniques and novel techniques.

Begin outlining and structure

I. Business

Questions about homework, assignments?

Next session's presenters-- Suzanne Martinez, Linda Atlas, ?? Dreama??

Changes for presentation schedule? Does everyonle have two times, if they want it? (??Marc??)

Survey Monkey coming tomorrow–just for me.

— Works best for you?

— less great?

— anything else to cover that we didn't do yet?

Short Marketing discussion on 10-28-20. Please email questions to be addressed.

II. Presenter I: Philip or Marc

III. Logistics & Long and Medium Shots

The Drunken Cowpoke

Last week we wrote an exercise in small motor action.

Logistics is about movement too, but it is the movement of large groups of people or things, or about people moving through space. Like group scenes, the multiplicity of moving parts makes this difficult to get right.

Read these short passages, examples of logistics and crowd control.

The first one is a newspaper account from the 1930's that attempts to describe something that was new at the time: air attacks on civilians. It is about an event that Picasso made famous in his monumental painting Guernica.

The second one is two versions of someone coming into a bar. One is written to give the layout of the room in a more-or-less cinematic way. The character scans the place and gives us a sense of what is going on, who is standing where. The second version has a vertiginous effect. Things are seen out of order. It is a point of view that shows the character is under stress or possibly drunk or drugged.

The final passage is from one of my novels, Oradell at Sea. I was attempting to do a little of all that: make the big picture of what is happening clear, but also limit what we see to what the main character sees. It's set in the dining room of a cruise ship. (Is anyone every going to go on a cruise again??).

IV. Some Tricks for crowd scenes:

Finally, here are a couple of practical ways of dealing with logistics and large groups. I probably shouldn't talk about tricks-- all prose narrative, after all, is an illusion of reality-- but as you revise, you can try these things to make the story telling run more smoothly.

Only identify two or three individuals in a scene. Say "The twenty two members of the Ridgewood Bobcats walked into the dressing room with long faces," and then give quoted speeches only to Rob, Andre, and the Coach. The other Bobcats can mutter as a group, or lower their heads in shame, but they remain a mass, part of the scene setting.

Only give proper names to the most important characters in a group scene. (As above. Be sure you really need the names. Proper names call attention to themselves.)

Clarify the logistics and physical action by giving a firm point of view. Imagine a fixed camera or a character in a chair in the northeast corner next to to the white board. Write only what is seen from that point of view. This will help keep the reader oriented. If that point of view or fixed camera angle is blocked by a pillar, don't tell what can't be seen. Even if you have a multiple viewpoint story, write your action from one point of view.

Conflate. If you are writing fiction based on you own large real family, for example, conflate two annoying little brothers into one. It strays from the facts, but allows the creation of one full character and eases your logistical problems.

V. Write (logistics large)

This week, a birdseye or midshot view: people in your novel in action: a fight, first sight of a city with people moving around.

VI. Share?

VII. Break

VIII. Presenter II: Philip or Marc

IX.

X.WRITE:

1. Describe the cover of the novel

2. A character in your novel is having inappropriate feelings/reactions: feeling distinctly ungrateful at Thanksgiving; a murderer's inappropriate anger leading to violence, etc.

XI. Asignments for Next Week:1) A character in your novel has an inappropriate reaction.An outline of your novel. Or....

2) Write an outline of your novel.This can be sentences or a formal Roman Number outline or a chronology--or even a drawing or map of your book. Or...

3)Substitute pages of your novel.

Read: Selection from Ten Strategies, Outlining from Ten Strategies; also Suzan Colón's "Stakes" Method of Outlining.

Optional Reading: In Ten Strategies, read "Strategy 6: Structure Your Novel." Check especially starting p. 96 "The Best Time to Start Outlining."

Session 7: 10-21-20

Structure and the Novel I:

When, How, & If to Outline

Assignments due today:

Write (Choose one of these):

1) A character in your novel has an inappropriate reaction. Or....

2) Write an outline of your novel.This can be sentences or a formal Roman Number outline or a chronology--or even a drawing or map of your book. Or...

3) Substitute other pages of your novel.

Read: Online Selection from Ten Strategies, Outlining from Ten Strategies; also Suzan Colón's "Stakes" Method of Outlining

Optional Reading: In Ten Strategies, read "Strategy 6: Structure Your Novel." Check especially starting p. 96 "The Best Time to Start Outlining."

I. Business

Next session's presenters-- Clea Rivera (double turn), Linda Atlas

Changes for presentation schedule ?

Short Marketing discussion next week-- 10-28-20. Please email questions to be addressed.

Survey Monkey/evaluation Results

II. Outlining: All of this is about 1) structuring and shaping a long work and 2) keeping track of the many parts of a long work.

Some Sample Outlines:

Outline sample 1.pdf

Outline sample 2.pdf

Outline sample 3.pdf

Outline sample 4.pdf

Outline sample 5.pdf

Outline sample 6.pdfOne is a form that a writer created to help draft each chapter in the book. One is from my non-fiction book about writing a novel, which is fairly straightforward, based on teaching and workshops I've done, and much less of a struggle than my fiction outlines. . Another is from a science fiction novel of mine, and it's what I call a "running outline," that is, I update it at the end of a day's work--doing the page count, word count, date, and also making any changes (names, facts) that I came up with that day. One is a student "outline" that is really a diagram of characters that helped her in her thinking--and that's the main point of an outline: to help you visualize what you've done and to hypothesize about what you might do--and remember ideas for the future. You need to find your own best outlining method.

Chronology-- for planning and getting ideas.

The Present of the Story: the chronological location in your writing, as distinguished from. say, foreshadowings, but particularly from flashbacks..

The hypothetical: You make up a hypothetical or test plot. Write down a beginning, middle, and end. Write as if that made-up plot were your plot, but be ready at any moment to change it. This gives you a structure to work with (especially an end point) but gives preference to changes that your imagination might come up with

A running-outline from one of my novels (scroll down to "Oradell at Sea Outline") The point of this file in my computer is that it changes at almost every writing sessions. I save it periodically, for historical interest. I record progress, make notes to myself. . Note how it includes a chronology

Arc of Story (as discussed a week or two ago): too general for most novels, but should be done periodically. What is the dramatic high point of your novel? Which scenes lead to it?

Alison's "Penny Board" (an in-process, dynamic thinking-through-pictrures board). This could also be doodles or drawings or a Venn diagram. These are all ways of thinking about your novel, of getting a general grasp of it.

Paper and post-its for planning

:The archepelago method

Chapters are largely arbitrary, arranged for ease of reading, more or less short story length. I believe that the true building block, the structuring element, of a novel, is the scene, just as it is in those other dramatic genres, film and theater. One of my favorite ways of thinking about a novel is as an archipelago, the tips of an underwater mountain range that rise out of the sea as islands. Imagine each island as a scene. We take a ship, or even better, a double hulled canoe like the ancient Polynesian settlers, and travel from one island to the next. Our vessel in the water is the narration and the other materials that connect the scenes. They are essential, but the high points, the dramatic peaks, take place on the islands.

III. Presenter I: Linda

IV. WRITE

Put a moment of loneliness in your novel. Perhaps for a scene you've already written. Character can be alone, or maybe just feeling alone.

V. Break

VI. Presenter II: Suzanne

VIII. Presenter III: Dreama

IX. Assignments for Next Week

Writing Assignmnent: Write the Climactic Scene of your novel especially if you are nowhere near the climax in your ddrafting! Or, as always, provide me with pages for response.

Reading assignment Background for the marketing discussion::Review of The Death of the Artist by William Deresiewiczs. This is about the future of artists, including novel writers.

Session 8. 10-28-20

Marketing and Structure II:

How Is Your Novel Shaping Up?

What Will You Do with It once you've finished writing it?

Writing Assignment: Write the Climactic Scene of your novel especially if you are nowhere near the climax in your drafting! Or, as always, provide me with pages for response.

Reading assignment:Review of The Death of the Artist by William Deresiewiczs. This is about the future of artists, including novel writers. Background of the marketing discussion.

I. Business

Next session's presenters-- Marc Rapaport; David Martin; Michelle Vidal

Everyone remembers your final presentations ?

Suzanne Martinez shares information about a contest for writers:

Here's the link for the writing contests I mentioned....I found out about it from some writers I met a Kenyon a couple of summers ago in the good old days when you could actually attend a writers' workshop in person.

I've enjoyed participating, especially in these crazy times when getting out is hard. This allows you to go somewhere you'd never planned in wrestling with the challenging prompts and making the deadlines.

I just completed Round #3 in the Flash Fiction Challenge and a few weeks ago submitted Round #1 in the Short Screenplay Challenge. One of the best features is the feedback each writer receives from 3-4 judges for each story you submit. So far, two of my NYC Midnight stories have been accepted for publication. http://www.nycmidnight.com

II. Presenter I: Clea (double)

III. Marketing discussion Today

Marketing/Next Steps

It is a time of great flux, lines weakened between commercial publishing and so-called indie publishing which is sometimes self-publishing, sometimes subsidized or shared. Many models that you'll need to research on your own.

The ideal, which I was at the very end of, is agent who takes on book, sells to editor, who sells to her publisher, who edits, prints, sells the books, arranges your tour, and sends you checks. For some, still happens. Good luck!

Now, even with a commercial publisher, they want your "platform" and sometimes copy editing.

(But I have to say, even when I had a hotshot agent who placed my first novel with Scribner's, I placed my children's and literary short story book on my own. Agent just went over contracts and took a cut.)

Since then, I've published with small presses that paid nothing; university presses that don't do advances, but pay a cut; also part of a cooperative press originally for republishing, and more.

Here are some things to do as you get closer to being ready to market your novel:

First, get it in pristine condition--they have no patience for mess and mistakes. They are looking for excuses to reject.

Experiment with submitting to online journals and magazines. Lots on the internet.

Do your research! Read Jeff Herman's guide to agents. Read old standards like Writer's Market and The Writer and Writer's Digest and get on Jane Friedman's free newsletter etc. And take a look at the very cheap downloadable Poets & Writers $4.99 Book about the Process of Publishing

Go on Facebook and search for "Calls for submissions (poetry, fiction, art.)" Sign up to get notices.

Here's some more online information about submitting and marketing your work in the age of e-books and self-publishing:

Look at the resources at my t Draft Notes on Getting Published (includes a continuum of types of publishing)/

Notes on various types of publishing at Publishing Types and Print on Demand.

How long should a novel be? See Resources for Writers page.

See blog post by Veronica Sicoe on why she self-publishes.

A Wall Street Journal article about Marlen Bodden, a former student in one of my novel classes who first self-published-- and then had her book picked up by a commercial press. Note: self-publishing should never be you first choice, but it should be on your list of possibilities.

One page of mags, books, links about getting published (Some of this is out-dated: please send me any dead links you find or alternative information).

Some Questions:

From Clea:

1) I am interested in learning more about the role of an editor. How involved are editors? What is the process of finding an editor whom one works well with? Are they assigned by a publisher? Is there ever a situation in which one can submit work, without an editor?

2) Publishers: How does one go about finding a publisher? What are the steps, what is the protocol? And once one has a publisher, how does the process work?

3) And what is the agent's role in all of this?

From Philip:

Do aspiring writers have to be represented by a literary agent?

From Suzanne:

On author bios in cover letters for literary publications--should study at workshops be included or just MFA study?

If no MFA, should only publications where work was accepted be listed?

Is it critical to have a substantial resume of past publication by well regarded literary journals before approaching an agent for a novel or is the query letter with the pitch more important?

How many times would be reasonable to submit a story and have it declined before shelving it or doing a major revision?

From Dreama:

How about the effects of the pandemic? I have not been in a hurry to publish since the pandemic began.

She recommends MSW's website on publishing (Resources for Writers)

My local Virginia Writers Club has had a speaker who makes tons of money on Amazon. It's the subject: fantasy.

My best markets: teacher groups, library, and book stores.

From Alison:In attending the Algonquin NY Pitch Conference last spring, (virtual) several people were advised not to even mention past publications if they performed poorly in the marketplace. Re having short stories published, is it best to go for quality or quantity? Polish fewer things and aim for better journals/ magazines, or have more pieces accepted by less prestigious publications?

Other questions from past classes:

How do you copyright your novel to prevent someone from stealing the ideas and content?

Go online to http://www.copyright.gov for the latest information. HOWEVER, from the moment you finish a piece of writing, the government recognizes that only you can decide how to use it. The law presently governing this is the copyright law of January 1, 1978. A piece of writing is copyrighted the moment you put it to paper. You may indicate your authorship with the word Copyright (or the c sign), the year, and your name, but this is not necessary. Protection lasts for your lifetime plus 50 years. If your work is anonymous or pseudonymous, protection lasts for 100 years after the work's creation or 75 years after its publication, whichever is shorter. None of this holds in the case of writing-for-hire. You do not have to register your work with the Copyright Office to receive protection. If you want to, however, you may request the proper forms from the Copyright Office, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20559.

Would self publishing be an option rather than go through all the rejections unknown writers are likely to receive? If so, are there companies you can recommend?

What is the right number of agents to query at one time? They take so long, and not all of them even reply. Is there any reason not to send to a hundred in one gulp?

In the notes about one agent, she wrote "Please, please don't sent stories about white dudes on quests." That covers a lot of ground. I am all for diversity but still hope to be published. Any advice on how to negotiate this variable?

How are publishing houses doing and what adjustments will they have to make now?

Are any of them actually making efforts to market one's book or is it up to the author to manage everything?

Extra (I haven't checked these out--from a friend--mostly from Authorspublish.com)

"18 Major Book Publishers Always Open to Submissions" - https://www.authorspublish.com/18-major-book-publishers-always-open-to-submissions/

"The Problem with Mass Submissions" - https://www.authorspublish.com/the-problem-with-mass-submissions/

MudRoom - Call for Submissions -https://www.mudroommag.com/general-submissions

"Eerdmans Books for Young Readers: Now Accepting Manuscript Queries" -

"How to Negotiate Your Way Out of a Publishing Contract" https://www.authorspublish.com/how-to-negotiate-your-way-out-of-a-publishing-contract/

IV. Break

V. WRITE

Someone in your novel is trying to sell something to another person. This can be an actual retail object, or life insurance, or a political candidate-- or something like one's self at an interview, or one's self as a potential sexual partner.

VI. Presenter II: Linda

VII. Assignments for Next Week

Writing Assignments-- you choose:

Choice One: A revision based on comments in this class. Include notes from MSW and class members for comparison.

Choice Two:

--A good "outlining" exercise is to write one sentence summaries of 7 (arbitrary number, of course) of the most important scenes in your novel--already drafted or not. That is, you may be hypothesizing scenes. Remember, this is dramatized scenes that will be continuous time, with dialogue, action, etc. Something happens. Just name or indicate what they are.

--Later, perhaps after the class is done, draft those seven scenes, however roughly. You then have seven scenes at widely varied spots in the novel, and one strategy is to write next what connects them. If you have enough scenes, this can give you a very rough but structurally sound early draft of your novel.

Choice Three:

Any pages you want response to.

Reading Assignments due (for revision discussion):

Seven Layers to Revising Your Novel ( from The Writer (November/December 2012, Vol. 125, Issue 11).

Session 9. 11-4-20

Revision Techniques

Especially Useful for Novels

Alison Hubbard sent us the link to the famous New York Pitch Conference.

Suzanne Martinez has a story in Flash Fiction Magazine!

Writing Assignments due today-- you choose:

Choice One: A revision based on comments in this class. Include notes from MSW and class members for comparison.

Choice Two:

--A good "outlining" exercise is to write one sentence summaries of 7 (arbitrary number, of course) of the most important scenes in your novel--already drafted or not. That is, you may be hypothesizing scenes. Remember, this is dramatized scenes that will be continuous time, with dialogue, action, etc. Something happens. Just name or indicate what they are.

--Later, perhaps after the class is done, draft those seven scenes, however roughly. You then have seven scenes at widely varied spots in the novel, and one strategy is to write next what connects them. If you have enough scenes, this can give you a very rough but structurally sound early draft of your novel.

Choice Three:

Any pages you want response to.

Reading Assignments due (for revision discussion):

Seven Layers to Revising Your Novel ( from The Writer (November/December 2012, Vol. 125, Issue 11).

I. Business

1. Nothing accepted after last day, November 18, 2020.

2. Any left over questions from marketing discussion?

3. Presenters' pieces for 11-18-20 due to class by 11-11-20

II. Presenter One:

Michelle Vidal

III. Revision Discussion I: Micro Revising

Micro revising (similar for all types of fiction, and actually, all prose narrative--personal essay, etc.)

IV. Presenter Two

David Martin

V. Break

VI. Revision Discussion II: Macro Revising

A. How do you feel about revising? Dread it? Look forward?

Revision is (IMHO) Adding, Cutting, Moving around. I

B. Specific ideas for revising a novel.

Main thing to remember: you don't (and probably shouldn't) go back and start at the beginning every time. In particularly, I suggest (once you have a draft or something like it):

-- Go over the last third or quarter first.

-- Go through like a reader

-- Go through using the hunt function on your word processer for various elements: a character; a city; an object.

C. More ideas:

Seven Layers to Revising Your Novel

VIII. Presenter Three

Marc Rapaport

IX. Final Homework (nothing accepted after 11-18-20)

Choice One:

Any pages you want response to.

Choice Two:

Put religion in your novel...

Choice Three:

People are discussing politics. This can be a distraction from what your main character really wants to talk about; it can be a screen for what people are really feeling. It can be a moment when a character feels ignorant or out of places. It can be the radio in the background. Whatever you want, as long as it's politics.

Choice Four:

If you haven't done it yet, a revision based on comments in this class. Include notes from MSW and class members for comparison.

No Class

November 11, 2020

Session 10. 11-18-20

Final Session

MSW will receive homework and extra pages through midnight 11-18-20, but not after that. She'll return them to you as soon as possible, with good luck before Thanksgiving.

Homework Due:

Choice One:

Any pages you want response to.

Choice Two:

Put religion in your novel...

Choice Three:

People are discussing politics. This can be a distraction from what your main character really wants to talk about; it can be a screen for what people are really feeling. It can be a moment when a character feels ignorant or out of places. It can be the radio in the background. Whatever you want, as long as it's politics.

Choice Four:

If you haven't done it yet, a revision based on comments in this class. Include notes from MSW and class members for comparison.

A few novelists I've been reading lately.

Who do you read most often?

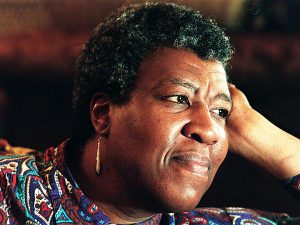

Octavia Butler, Tana French, Mrs. Humphrey Ward, Dennis Lehane, George Eliot, Julie Otsaka, Walter Mosley

I. Business

1. Any changes re: grades?

2. People I have work from--hope to return before Thanksgiving.

3. Tonight our presenters and perhaps a little more discussion than usual.

4. General business questions?

II. Presenter One

Philip Ai

III. Mini-lecture 1--Writing a novel is hard, and it takes a long time....

When you feel like burning your computer and going out for a beer (or at least to the refrigerator for a beer) instead of writing, give yourself some slack: some do it fast, some take years. Nobody says it's easy.

DISCUSSION: What is hardest for you in the process?

IV. Presenter Two

Dreama Frisk

V. Break

VI. Mini-lecture 2-- Flashback

Janet Burroway in Fiction: A Guide to Narrative Craft says: "Flashback is one of the most magical of fiction's contrivances, easier and more effective in this medium than in any other, because the reader's mind is a swifter mechanism for getting into the past than anything that has been devised for stage or even film....Nevertheless, many beginning writers use unnecessary flashbacks. This happens because flashback can be a useful way to provide background to character or events, and is often seen as the easiest or only way. It isn't. Dialogue, narration, a reference or detail can often tell us all we need to know, and when that is the case, a flashback becomes cumbersome and overlong, taking us from the present where the story and our interest lie.... "

Here are some materials on flashback

VII. Mini-lecture 3-- Grounding and Verisimilitude (didn't get to do this)

Verisimilitude is something I find myself querying in your home works and presentation pieces. The word does not mean "realistic" or "natural." Rather, it's whatever it takes to make a reader believe what they are reading. It means "the appearance of reality." In other words, does the illusion work? Does it seem true? Does the character seem 15 years old? Does she really seem like someone who has been homeless for two years?

Some very quotidian things readers usually need are things like characters' ages; what the characters look like (this can be very minimal--"with his long greasy red hair"; what century or world we are in. You may be quite general here--"Long ago and far away"-- and you may choose to leave a lot of uncertainty. The issue is to keep the uncertainly intriguing--how to tie it just close enough to something concrete so that the reader doesn't drift off.

.

Pacing is one of the trickiest parts of creating verisimilitude. Most of us just depend on our experience as readers to know how long a scene should take or how much to include, but as you revise, try to be thoughtful about your illusions. Sometimes it is enough to say, "Ten years passed...." Or, at the end of a struggle, the hero gets knocked out, there's some white space, and he wakes up and tries to figure out where he is and why he is bound with ropes.

More difficult is figuring out how long the struggle should go on to make it seem real but also to give an overview of what is happening. You want it to be very clear what is happening even if the character is drugged or confused! Good luck with that...

Verisimilitude is closely related to "grounding," which has to do with putting the reader's feet on the floor of a particular decade or distant planet. In my science fiction books I have (not terribly originally) made the planet have two suns, one pink and one blue. This makes me conscious of what color the shadows in the desert are, and this in turn helps keep me on that planet in my story and imagery.

In a novel I wrote that takes place in part during the second world war, I did a little light research with a box of crumbling newspapers at my mother's house. I found a nineteen forties newspaper and, since I'd given the main character a job in a movie theater, I thought I could find what movies were playing and what movie stars. She was a teen-ager, and the movie stars gave me the idea of comparing the stars to the real men and boys in her life. around her. So my research, slight as it was, helped develop character and story line as well as getting a few facts straight. It gave me more: I found an ad for a brand new floor model radio that I added to the décor of an affluent family's house. I also was reminded that women (and men) in the 1940's wore hats! Not only did people wear hats, but women were indulging that year in a style called a "picture hat" which had a huge round rim that was supposed to show off your pretty face. This gave me a scene in which the main character has trouble getting into a car because of her hat.

This is small stuff, but small stuff is precisely what grounds your reader. The things we touch and eat and sit on and wear are for novelists also what fuels our imaginations. It doesn't matter where the details come from, but if you don't have them, the grandest architectonics and the most gripping plot will feel sketchy and incomplete. The world of your novel will feel like someone's personal fantasy rather than a vivid fantasy world we can all imagine being part of.

VIII. Write

Last week I gave as homework one of the great forbiddens for discussion in "polite" conversation-- politics or religion.

This time, let's be more specifdic: put a moment of epiphany in your novel. This could be some character's religious or philosophic epiphany, or it could be a character's realization ("I think I love her!"); or something about the plot ("Is it possible that he is the rat?")

SHARE

IX. Write/Thought Exercise

What will you be doing with the novel in six months?

Share

X. Farewells

Schedule of Presenters

9-16-20

Alison Hubbard

Suzanne Martinez

9-23-20

David Martin

9-30-20

Michelle Vidal

10-7-20

Alison Hubbard

10-14-20

Philip Ai

Marc Rapaport

10-21-20

Suzanne Martinez

Linda Atlas

Dreama Frisk (short)

10-28-20

Clea Rivera (double turn)

Linda Atlas

11- 4-20

Marc Rapaport

David Martin

Michelle Vidal

No Class 11-11-29

11-18-20

Dreama Frisk (double)

Philip Ai

Top Row: Lavie Tidhar (interesting speculative/science fiction); Tana French (the fictional Dublin Detectives).

Bottom Row: Walter Mosley (Easy Rawlins crime mysteries); Julie Otsuka (exquisite prose, wrote in voices of Japanese women immigrants to U.S.); J.G. Ballard (weird futuristic stuff and one semi-autobiographical masterpiece Empire of the Sun).

Below This Line: Various NYU Policies and Information

Posted Here Per NYU Requirement.

Novel Writing

Instructor: Meredith Sue Willis

Email: meredithsuewillis@gmail.com

Course Number: NYU WRIT1-CE9355 Novel Writing Meredith Sue Willis

Term: Fall 2020

Class Format: Synchronous via Zoom

Course URL: www.meredithsuewillis.com/nyunovelwritingfall2020.html

Course Meeting Pattern: Wednesdays, 6:30-8:50 pm. No class November 11, 2020

General Course Information

Faculty Name/Title:

Faculty NYU email address: Meredithsuewillis@gmail.com

Response time and Communication: Email, usually within 24 hours.

Course Description

Receive the help you need to get started and to get structured, whether your goal is to write a novel or to mold a series of short stories into a longer work. In this course, delve into writing exercises that practice establishing tone, exploring character, tightening and deepening dialogue, and adding interior monologue. Topics covered include sustaining interest as a writer and a reader, understanding the value of an agent, and excerpting from a lengthy work for publication in magazines. This course is appropriate for anyone who has done some writing or who has taken an introductory writing course.

Course Prerequisites

Command of written English and a desire to write fiction; an an interest in reading and writing novels.

Course Learning Outcomes

- Advance your novel by 30 - 50 pages.

- Write an outline or other plan for your novel

- Learn the basic vocabulary and issues for thinking about novels

- Improve your ability to critique and revise your own work and how to support the work of others.

COMMUNICATION METHODS

MSW prefers to communicate by email, and generally will respond within 24 hours, except on weekends and holidays. If she plans to be away from my computer for more than a couple of days, she will let you know in advance. Should you encounter any issues with the course, please contact MSW as soon as possible. Use her regular email, meredithsuewillis@gmail.com.

Announcements

Please check the class web page at https://www.meredithsuewillis.com/nyunovelwriting%20fall%202020.html frequently for minor changes, additional optional readings and other changes. Major changes (cancelled class etc.) will be announced by email and on the “Announcements” module on NYU Classes within the course.

TEXTBOOK and COURSE MATERIALS

Optional Text

Ten Strategies to Write Your Novel Meredith Sue Willis, Montemayor Press (www.montemayorpress.com) 2010, ISBN 9781932727104 There will be other readings online with links from the class web page.

COURSE STRUCTURE

This course will be conducted synchronously on Zoom, using the class website at https://www.meredithsuewillis.com/nyunovelwriting%20fall%202020.html;

NYU Classes ;and the Zoom Virtual Classroom. To access your course on Zoom, log in to NYU Home with your NetID and Password. Then, select NYU Classes. You will access the Zoom Virtual Classroom through NYU Classes.

Novel Writing is organized in ten sessions that will include live discussions by zoom; readings to be done outside of class; readings during class using web links and shared screen; short in-class writings; very short mini-lectures; critiquing of student writing.

There will be weekly assigments, all from the student’s novel-in-progress. Students aleady engaged in a novel may substitute selections of their novel for the assignments.

For a detailed look at some sample pages of a past Novel Writing class, look at https://www.meredithsuewillis.com/nyunovelwriting%20spring%202020.html .

For more about the instructor, check out her web page at https://www.meredithsuewillis.com.

COURSE EXPECTATIONS

Students are expected to look at the class webpage at least weekly for changes, updates, and links to readings. These will be found at https://www.meredithsuewillis.com/nyunovelwriting%20fall%202020.html . Homework assignments should be double-spaced with one inch margins on all sides and a font similar to Times New Roman 12 point, @ 2 pages long (up to 600 words). The homework assignments are for the professor only. She will respond holistically. You will also be expected to present your work to the whole class two times. These will be longer chunks of your novel. The total number of pages the teacher will look at will be 50, including both longer chunks and homeworks.

Attendance

You are expected to attend all classes, as the course depends on class discussion.

Also take a look at

Class Conduct

Here are some of NYU’s suggestions for courtesy and professionalism in virtual classes. Some of these are pretty funny, bringing up thoughts about wearing pajamas to class. I always wonder if pajama bottoms with a button down shirt are okay. This is just food for thought….

- When you are typing or submitting a chat response, do not use all capital letters (caps). Caps is equal to SHOUTING YOUR MESSAGE.

- Although it is customary to use acronyms (ex. ROFL - rolling on the floor laughing, BTW - by the way, or FYI - for your information) when chatting online, try to avoid using these. There may be those in this course who are not as experienced as you and may miss out on understanding.

I (your instructor) was just embarrassed in a Zoom meeting about children and racism when I didn't understand BIPOC. I thought it was about gender and it's Black Indigenous People of Color. Novels, stories, personal narratives, poetry and much more work best when they don't make assumptions and are very concrete.

Web Conferencing:

- Dress as if you are in the Classroom.

- Keep your microphone muted unless asking a question or engaging in discussion.

- Check your video and audio when entering your class session.

- Think background, minimize distractions around you.

- Look into the camera instead of looking at the screen.

This is tough: Your instructor really doesn't like not being able to see what's going on at the periphery.

- Type quietly, mute if necessary.

- Don’t eat during a Zoom class session.

- Focus on Class.

SPS classes are diverse and include students who range in age, culture, learning styles, and levels of professional experience. To maintain an inclusive environment that ensures all students can equally participate with and learn from each other, as well as receive feedback and instruction from faculty during group discussions in the classroom, all course-based discussions and group projects should occur in a language that is shared among all participants.

Time Commitment

Classes run 2 hours and 20 minutes with a break. Your outside reading shouldn’t take more than half an hour, probably less. What may take a little more time is responding to the work of other students for critiquing sessions. The focus here is on you getting underway or restarted on a novel, so writing is where most of your time should be spent. The more you write, the more you get out of the class. It’s all up to you.

Class Participation

You’ll get more out of it if you participate. Critiquing, in particular, needs everyone to read the other students’ work and be prepared to talk about it. The more you give, the more you'll get.

Assignments and Deadlines

The short weekly assignments and the papers for critique are due by the end of business on Friday . This gives you extra time: in-person classes have work due on the day of class.

Grading Policies

You may choose to take this course pass/fail by applying to the office of CALA. The truth is, grading creative writing is a ridiculous proposition, and the grading in this class is actually not going to be on your writing, but on your use of the class. If you really want or need a grade, it goes like this: If you do all the homeworks, attend all the class sessions, show evidence of having read all assignments, presented your work for critique at least two times, and are an active, supportive member of the group, you’ll get an A. Not doing any of those things takes you down to a B or lower.

Here are a lot of required notices from from NYUSPS:

NYUSPS POLICIES

“NYUSPS policies regarding the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), Academic Integrity and Plagiarism, Students with Disabilities Statement, and Standards of Classroom Behavior among others can be found on the NYU Classes Academic Policies tab for all course sites as well as on the University and NYUSPS websites. Every student is responsible for reading, understanding, and complying with all of these policies.”

The full list of policies can be found at the web links below:

University: http://www.nyu.edu/about/policies-guidelines-compliance.html

- Student Affairs and Reporting- https://www.nyu.edu/about/policies-guidelines-compliance/policies-and-guidelines/student-services.html

NYUSPS: http://sps.nyu.edu/academics/academic-policies-and-procedures.html

Students With Disabilities

If you are a student with a disability who is requesting accommodations, please contact New York University’s Moses Center for Students with Disabilities (CSD) at 212-998-4980 or mosescsd@nyu.edu. You must be registered with CSD to receive accommodations. Information about the Moses Center can be found at www.nyu.edu/csd. The Moses Center is located at 726 Broadway on the 3rd floor.

Health and Wellness

To access the University's extensive health and mental health resources, contact the NYU Wellness Exchange. You can call its private hotline (212-443-9999), available 24 hours a day, seven days a week, to reach out to a professional who can help to address day-to-day challenges as well as other health-related concerns.

Bias Response Line

For any concerns about bias at NYU, contact the NYU Bias Response line at 212-998-2277 or at bias.response@nyu.edu. Or complete the online form at https://www.nyu.edu/about/policies-guidelinescompliance/equal-opportunity/bias-response/report-a-bias-incident.html.

This content was originally created by NYU Stern. It has been modified slightly to be more relevant for Tandon faculty and students. The document draws heavily from a document used at NYU Law School, which was the result of a collaboration among NYU Law’s Diversity Working Group, Student Bar Association, and All-ALSA Coalition, and draws upon numerous expert resources including Claude M. Steele, Whistling Vivaldi (2010).

Academic Integrity and Plagiarism Policy

All students are expected to be honest and ethical in all academic work. This trust is shared among all members of the University community and is a core principle of American higher education. Any breaches of this trust will be taken seriously. A hallmark of the educated student and good scholarship is the ability to acknowledge information derived from others. Students are expected to be scrupulous in crediting those sources that have contributed to the development of their ideas.

Plagiarism involves borrowing or using information from other sources without proper and full credit. Students are expected to demonstrate how what they have learned incorporates an understanding of the research and expertise of scholars and other appropriate experts; and thus recognizing others' published work or teachings—whether that of authors, lecturers, or one's peers—is a required practice in all academic projects. Students are subject to disciplinary actions for the following offenses which include but are not limited to:

- Cheating

- Plagiarism

- Forgery or unauthorized use of documents

- False form of identification

Use the link below to read more about Academic Integrity Policies at the NYU School of Professional Studies. Academic Policies for NYU SPS Students

Student Resources

The University reserves the right to deny registration and/or graduation and withhold all information regarding the record of any student who is in arrears in the payment of tuition, fees, loans, or other charges (including charges for housing, dining, or other activities or services) for as long as any arrears remain. Students may contact the Bursar's Office at 212-998-2806 to clear arrears or to discuss their financial status at the University.

Students seeking academic help in their studies can use university resources in addition to an instructor’s office hours. University Resources include the Academic Advising, Writing Center, Career Center, Tutoring Center, Learning Center, and Student Affairs. The centers provide services such as tutoring, writing help, critical thinking, study skills, degree planning, and student employment.

For a complete list of student resources, Students can visit the NYU SPS Office of Student Affairs Resource and Services page.

SCHOOL GRADING POLICIES

Grading is by letter grade: A, A-, B+, B, B-, C+, C, C-, D+, D, and F. This is the link for NYUSPS’s complete academic policies for noncredit courses: https://www.sps.nyu.edu/homepage/student-experience/policies-and-procedures.html#CareerAdvancement3

Letter

%

GPA

Meaning

A

93-100

4.000

Excellent: Earned by work whose excellent quality indicates a full mastery of the subject and is of extraordinary distinction.

A-

90-92

3.667

Excellent: Earned by work whose excellent quality indicates a full mastery of the subject.

B+

87-89

3.333

Good: Earned by work that indicates a very good comprehension of the course material, very good command of the skills needed to work with the course material, and indicates the student’s full engagement with the course requirements and activities.

B

83-86

3.000

Good: Earned by work that indicates a good comprehension of the course material, good command of the skills needed to work with the course material, and indicates the student’s full engagement with the course requirements and activities.

B-

80-82

2.667

Good: Earned by work that indicates comprehension of the course material, command of the skills needed to work with the course material, and indicates the student’s engagement with the course requirements and activities.

C+

77-79

2.333

Satisfactory: Earned by work that indicates an adequate and satisfactory comprehension of the course material and the skills needed to work with the course material, and indicates the student has met the requirements for completing assigned work and participating in class activities.

C

73-76

2.000

Satisfactory: Earned by work that indicates a satisfactory comprehension of the course material and the skills needed to work with the course material, and indicates the student has met the basic requirements for completing assigned work and participating in class activities.

C-

70-72

1.667

Satisfactory: Earned by work that indicates a minimally satisfactory comprehension of the course material and the skills needed to work with the course material, and indicates the student has met the minimum requirements for completing assigned work and participating in class activities.

D+

65-69

1.333

Passing: Earned by work that is unsatisfactory, but that indicates some minimal command of the course materials and some minimal participation in class activities that is worthy of course credit toward the degree.

D

60-64

1.000

Minimum passing grade: Earned by work that is unsatisfactory, but that indicates some minimal command of the course materials and some minimal participation in class activities that is worthy of credit toward the degree.

F

Below 60

Failing: Demonstrates minimal to no understanding of all key learning outcomes and core concepts; work is unworthy of course credit towards the degree.

TECHNICAL REQUIREMENTS

Computer Hardware

Recommended Requirements

- Computer with at least 4GB of memory or more (RAM)

- Windows 8.0 or Mac OS X 10.9 (Mavericks) or higher

- Broadband (high-speed) internet access (direct connection or Wifi)

- Webcam and microphone (for online meetings)

Student Technical Skills

You are expected to be proficient with installing and using basic computer applications and have the ability to send and receive email attachments.

Software

- GoogleChrome (recommended browser for viewing online course materials)

- Mozilla’sFirefox (latest version; Macintosh or Windows)

- Adobe’sFlash Player and Reader plug-in (latest version).

- Apple’sQuickTime plug-in (latest version).

- Microsoft Office Suite (free for NYU Students).

- Zoom web conferencing tool

- Link to any additional software required.

NYU Classes Orientation and Training

To actively participate in this course, you will need to get familiar with the course environment. If you are not familiar with how to navigate this environment as a student or use any of these tools, please visit NYU’s Getting Started with NYU Classes page for a full tutorial on using NYU Classes.

NYU Classes Support

To receive 24/7 live support or deliver NYU Classes feedback, contact the IT Service Desk:

- Phone: 1-212-998-3333

- Email: AskIT@nyu.edu

- In-Person: Visit the IT Service Desk at 10 Astor Place, 4th Floor (M-F 9 am-6 pm EST)

- For support at NYU’s global locations visit www.nyu.edu/it/servicedesk.

Subscribe to Meredith Sue Willis's Free Newsletter

for Readers and Writers: